Man, you just can’t get away from these things. The modern world, and even most of the ancient world wouldn’t be the same without them. They have allowed mankind to navigate the Earth, build computers, make sound, and pin your mediocre test scores up on the refrigerator.

Because I’m such a dedicated person, I took the time to listen to Insane Clown Posse’s song Miracles (where I got the title of this post) so that you don’t have to waste your own valuable time to do it. Because it’s awful. The song is about appreciating the “magic” of natural wonders – stars, lava, giraffes, Niagara Falls, and the fact that the singer’s son resembles him, which apparently comes as some sort of surprise. Funny enough, the line that comes after “f***in’ magnets, how do they work?” (which is a great question, by the way) is “and I don’t wanna talk to a scientist. Y’all motherf**ckers lyin’, and gettin’ me pissed”. Well ICP, get pissed, cause here it comes.

Let’s take a look at our relationship with magnets, how they do the things they do, and the why behind the how they do the things they do. Confused? Awesome, lets go!

The History

Natural magnets were independently discovered and referenced in text by the Greeks in the 6th century BCE and the Chinese in the 4th century BCE. These people dug up lodestones – naturally magnetic bits of the mineral magnetite – and found that they had an ability to attract or repel bits of iron.

When it was discovered that they can orient themselves to the Earth’s magnetic field, they were suspended on string or rope to make the first compasses, and used in navigation. In fact, the word “magnet” originates from the Greek language and means “stone from Magnesia”, where a large number of lodestones were found.

Today, magnets and the use of magnetic fields are pretty much ubiquitous. Speakers, hard drives, credit cards, trains, motors, jewelry, toys, refrigerators – they all use magnets in some way. Figuring out how to use and manipulate magnetic fields has been integral in building a modern world, and in figuring out how our world works. Physicists have been using magnetic fields in experiments for decades – they can exert a force on charged particles, and superconducting magnets (a type of magnet that can produce a very strong magnetic field) are used in machines like the LHC to keep particle streams happily aligned.

The How

Generally speaking, there are two types of magnets: your typical permanent magnets, and electromagnets. Let’s take a look at permanent magnets first.

Permanent magnets are objects that are made up of materials that have been magnetized and can hold their own magnetic field. As you know, these guys can attract certain materials called ferromagnetic materials. These include iron, cobalt, nickel, and a few others; the same materials that magnets can be made from. All magnets are dipoles; they each have a “north” pole and a “south” pole. Based on our knowledge of electrical charges, where we see particles exhibiting a single charge (electrons are negatively charged and protons are positively charged), it would be logical to assume that magnets could behave the same way, but no monopole magnets have ever been found, and the discovery of a magnetic monopole would signal the discovery of a new elementary particle.

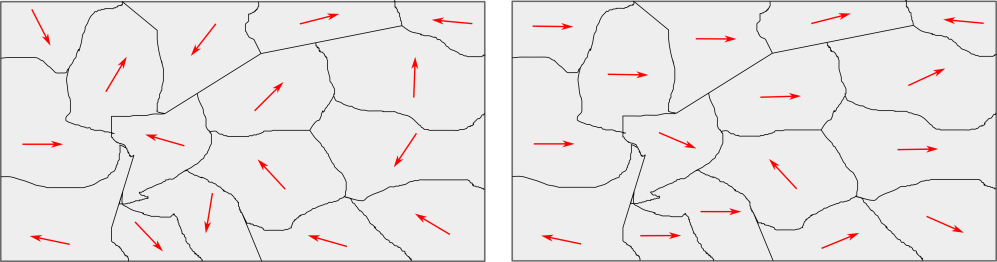

If you break a magnet in two, you’ll get two magnets each with their own north and south poles. It stands to reason that if you keep doing this, you’ll get a whole bunch of really small magnets, and that’s exactly what happens. We call these tiny bits magnetic domains – permanent magnets are made up of a collection of magnetic domains that contribute to the overall magnetism of the object. Randomly arranged magnetic domains can exist in any ferromagnetic material, but what makes permanent magnets special is that the magnetic domains are arranged in such a way that a dominant magnetic field arises from the sum of the magnetization from domains.

This happens when atoms, each with their own little magnetic fields (we’ll get into that later) influence each other to align and create a larger magnetic field, which in turn can turn more atoms nearby to align as well. This is how gang wars start, kids. Eventually, a magnetic domain will butt up against another and create a domain wall, the boundary between two magnetic domains. In a non-magnetic ferromagnetic material, domains are randomly oriented and all that fighting between domains causes the material to have little to no net magnetic field. A permanent magnet is akin to gangs banding together to achieve a common goal – create a single, dominant magnetic field. Or to hunt down one poor little gang trying to get home to Coney Island.

We can save most of the specifics for another day, but let’s talk briefly about electromagnets. In April of 1820, a Danish scientist named Hans Christian Oersted discovered something interesting: electric current (or electrons) flowing through a wire will create or induce a magnetic field around it.

This discovery led to the invention of the electromagnet, a coil of wire (called a solenoid) wound around an internal ferromagnetic (usually iron) core which helps to strengthen the magnetic field. When the current in the wire flows, an electromagnet behaves exactly like a permanent magnet – it has a magnetic field with two poles. What’s different is that when the current is shut off, the magnetic field goes with it, and the strength of the magnetic field can be adjusted by playing with the amount of current that you’re putting through the wire coil. Hang on to that idea of current inducing magnetic fields – you’re going to need it later.

How are permanent magnets manufactured you ask? There are a few ways to do it.

There is an interesting property of magnetic materials – when they’re heated to a certain temperature, their magnetic domains get destroyed. The material loses its own magnetization, and is susceptible to influence by another field. This temperature is called the Curie temperature (named after the famous Madam Curie…..’s husband), and it’s different for every material. So, a chunk of iron can be heated to its Curie temperature and cooled under the cunning manipulation of an outside magnetic field. When it wakes up, that chunk of iron will have been hypnotized into believing that it’s now a permanent magnet and will behave that way forever! Or at least, unless it’s heated up and ruined again. This is the most common way to manufacture industrial permanent magnets.

Even if you don’t apply an outside field, just cooling below the Curie temperature will restore magnetic domains, albeit with some randomized orientation, and a preferred orientation may arise.

Another method is to simply place a ferromagnetic material in a strong magnetic field for while and just let it cook. Eventually, it’ll retain a magnetic field when it’s removed from the applied field.

The Physics

This is where things get a little tricky. We’ve talked about atoms having their own little magnetic fields, now let’s talk about where those come from. As we all know, atoms are made up of a nucleus in the center of a bunch of orbiting electrons in a bunch of shells and sub-shells. These electrons moving around are what give rise to what is called a magnetic moment, which is sort of way to characterize the strength and direction of an object’s own magnetic field as a single vector and describes its tendency to align with outside magnetic fields. Just like in the electromagnet, the electron orbiting around in a little loop is like moving electrons through a coil of wire. It will produce it’s own tiny magnetic moment. A bunch of these little magnetic moments add up, and we get a magnetic field in the end!

Well, all atoms have electrons running around them, so why is it that not all materials are magnetic?

We can chalk it up to two things: electrons orbit in different directions so their magnetic moments can cancel out, and a little something called electron spin.

The first thing is somewhat intuitive – if you’ve got a pair of electrons and they’re producing magnetic moments in opposite directions, then you’ll get zero net magnetic moment at the end. Easy! Atoms are full of pairs of electrons, so magnetic moments are being cancelled out all the time. It’s only when there is a spare unpaired electron that’s allowed to do it’s own thing that an atom will have a net magnetic moment. Curious though, how these electrons always get paired up. Why?

That’s where electron spin comes into the picture. Let’s take it back to 1922, during the golden age of modern physics. At this time, everyone was all over this quantum mechanics stuff, and these two German dudes named Otto Stern and Walther Gerlach were no different. Stern and Gerlach came up with this experiment: they shot a bunch of electrically neutral atoms (silver, in their case) through an inhomogeneous magnetic field and onto a screen. An inhomogeneous magnetic field is a magnetic field that’s stronger on one side than the other. Long story short, what should have been a random smattering of silver on the screen turned into two distinct spots of silver instead. So what happened? Electrically neutral atoms travelling through a magnetic field should have just gone straight through.

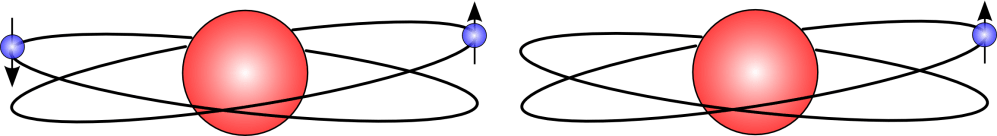

What Stern and Gerlach had discovered was that electrons have some sort of intrinsic property about them that produced a magnetic moment. We now know it as electron spin, so called because of the classical way to describe the production of a magnetic moment (electrons spinning around a nucleus). To be clear, electrons orbit around, and they have spin, but they’re not the same thing. The electron isn’t actually really spinning around it’s own axis, it only demonstrates a property that makes it seem like it is. It’s weird, but that’s quantum mechanics for you. The two spots of silver on that screen? Electrons exhibiting two different values of spin: and

, usually referred to as spin up and spin down and sometimes written or drawn as spin

and spin

. Basically, physicists insist on having symbols that are easy to draw because they’re very far away from being art majors.

A few years after the Stern-Gerlach experiment, a Swiss physicist by the name of Wolfgang Pauli proposed the idea that no two identical electrons can occupy the same quantum state simultaneously; electrons must have different spin values to fill the same sub-shell of an atom. His idea is known as the Pauli exclusion principle, and it got him a shiny Nobel Prize in 1945. Side note: The Pauli exclusion principle applies to all particles with half-integer spins, known as fermions.

A few years after the Stern-Gerlach experiment, a Swiss physicist by the name of Wolfgang Pauli proposed the idea that no two identical electrons can occupy the same quantum state simultaneously; electrons must have different spin values to fill the same sub-shell of an atom. His idea is known as the Pauli exclusion principle, and it got him a shiny Nobel Prize in 1945. Side note: The Pauli exclusion principle applies to all particles with half-integer spins, known as fermions.

An orbiting electron will align its own magnetic moment from spin to the magnetic moment that it produces when it orbits (coupling its spin direction and orbital movement in something cleverly called spin-orbit coupling ), and since the Pauli exclusion principle prevents two electrons with the same spin being in the same state, the other other electron will have to orbit in the opposite direction. So, you can have two electrons paired up in the same state or sub-shell, and those two electrons together (one spin up, one spin down) will have the magnetic moments they create cancelled. Any lonely electron that doesn’t have a partner to tango with can be free to let its induced magnetic moment shine through.

If you want to know more about how electrons fill orbitals, check out this page about Hund’s Rule.

Now it just comes down to atomic structure! Non-magnetic materials will have atoms that have mostly paired up electrons who are happily canceling each other out, while ferrous materials have atoms with fiercely independent electrons, ready to show their moments to the world. Get enough of these guys together and you’ve got yourself a magnetic domain, and we’re back in the HOW section of this whole thing.

It’s been a long road guys, and there’s a lot more to magnets than just that*, but I think this a good place to catch a breath. To sum up: the Pauli Exclusion Principle ensures that electrons come (at most) in pairs, and those that don’t are free to contribute to the magnetic moment of their atom. If they get along together and align, you’ve got a magnetic domain. Add a bunch of those, and you’ve got the permanent magnet that we all know and love.

I hope you enjoyed reading The Physics Behind…! Have some feedback? Awesome! I would love to know what you thought about this article, if you have any questions, and if you’ve got any suggestions for future posts. See you next week!

Sources: 1 2 3 4 5 6

Images: 1 2 3

*This subject is really quite complex, and would require more articles to get through completely. If you’re interested, look out for future posts about magnetism! There’s a lot to talk about!