Not that kind of hit. After a long winter, college football teams are gearing up for the next season and playing spring games left and right. American football is deeply ingrained in the culture of this nation, and during certain times of year, is all anyone is usually talking about. Every street corner of every college campus has someone half-assedly passing a football around while drinking cheap beer and burning cheap cuts of meat on cheap coal grills. It’s a little trashy, but really has heart. During NFL season, friends get together to rail on each other passionately about their fantasy football leagues whilst making fun of the kids hanging out and playing Magic The Gathering, as if those two followings have so little in common.

While I’m not usually the type to care much about sports (I don’t have a favorite NFL team, nor do I watch cricket), I did attend a big football school and I guess some of that spirit bled into me. Among all of the trademark events of modern American football: the kickoff, the drives, the plays, the runs, the passes, the abusive coaches, Gatorade dumps; tackles may be the most exciting. It’s almost as if we hold our breaths the entire game in the hope that our team will tackle, or avoid being tackled. This ritual seems to perpetuate our need for the moment of violent glory missing in most American’s every day lives. We crave it, so we fill it with violence on TV, movies, video games, and games in the Colosseum. I’m not against it. I love Game of Thrones, and just the other day I was yelling “Why won’t you just diieeeeeee!?” at aliens on Halo.

Now we usually don’t think about football in terms of its physics, but there is a lot going on when two players slam into each other. This week, we’re going to see how football was played in the past, explore the anatomy of a tackle, and check out the physics of momentum and impulse.

The History

American football has its beginnings in rugby and association football (soccer to us in the US) during the late 1800’s. These sports both had their beginnings from earlier versions of the game played in the UK, where a ball was either run or kicked over a line. Football as we know it started when Walter Camp, known as the father of American football, added rules about the line of scrimmage and downs to rugby and established it as its own distinct sport. Early football was popularized by colleges in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s, and professional football came around shortly after.

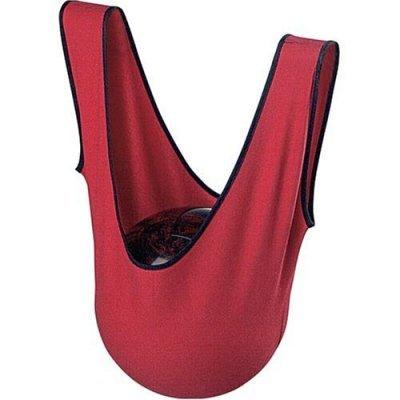

At first, football players basically wore little to no protection, a bit of legacy from its ancestral sports. Eventually though, people apparently thought it a little uncomfortable to be constantly running into each other without pads or helmets, and started to lend their brain cells and organs a little help. Leather and wool padding was sewn into jerseys, and leather helmets joined the team soon after. The 1950’s saw the introduction of plastic helmets and pads and over the years, advances in technology have improved gear even more, adding advanced synthetic materials, inflatable padding, and even sensors to help detect head trauma and track hits. Even with all this fancy stuff riding on the heads of players, concussions and injuries are still abound. You are after all, still subject to being thrown to the ground like a candy bar wrapper in New York City.

Though the tackle has been largely unchanged, knowledge about effective technique and safety has molded the ideal tackle over time, as well as influenced the rules of the game. Hopefully, the implementation of techniques and rules will continue to reduce neck and head injuries for both the tackler and…tacklee? Is that a word?

The How

As you’re gearing up for a tackle, you want to spread your feet to about shoulder width, keep your head up, get your back in proper alignment, and drive up through the tackle. Lets go through these and talk about how they pertain to physics. A wide stance lends more stability to your body. Anyone who has been on a bus knows that the people who aren’t prepared for a sudden stop or turn usually get tossed around and end up accidentally sitting on the lap of some poor old woman. Keeping your feet apart and starting low to the ground will allow you to spring up with a good solid base. The reason for maintaining the proper form in your head and back is twofold: keeping your head up prevents injuries to the neck, while keeping the back straight and body low allow for the most energy to be transferred through the body, which brings us to our next point. Driving up through the tackle by pushing hard against the ground will move more energy into your target, thereby stopping him in his tracks.

One way to measure the force of a tackle is with accelerometers that track the G force of a hit. G’s measure the acceleration of an object, and is equivalent to the acceleration due to gravity at the surface of the Earth. So, if you drop a football, it experiences 1 G on it’s way to the ground. If you throw a football with three times as much acceleration, you’d be subjecting it to 3 G’s. Launching the space shuttle also measures around 3 G’s but keep in mind that the rockets burn continuously, so don’t expect to throw a football into orbit. Executing a barrel roll in a fighter jet subjects the pilot to about 9 G’s over the course of the maneuver.

Launching shuttles and doing barrel rolls are pretty hardcore, so we’d expect a football tackle to be somewhere in the middle. But it’s much much different. Taking a good hit could potentially put 100 G’s on a player, with some of the most forceful hits reaching 150 G’s! Anything above 100 G’s is enough for a coach to take a player off the field and check for a concussion. This quick acceleration happens over a very short time, and the force of impact depends on the mass, speed, and time it takes for the tackle to bring someone down. If that sounds like we’re getting into the physics, it’s because we’re getting into…

The Physics

Right, what this blog is about.

We’re talking about two football players running into each other, which would be a collision. When we talk about collisions in physics, we have to talk about energy and momentum. As a quick refresher, energy is some quantity of objects that can be transferred from one object to another, and can do work of some sort. For example, we can put electrical energy to work to run motors. Thermal energy to boil water for coffee. In our case, we’re talking about kinetic energy, the energy associated a moving object, that does work when that object is stopped. We can quantify kinetic energy with the following equation:

,

where is kinetic energy,

is the mass of the object, and

is the velocity of the object.

As is evident, the kinetic energy depends on how massive the object is, and how fast it’s moving. However, take note that velocity has more say on the matter – if you double the size of a moving object, you’ll double its kinetic energy; double its velocity however, and you’ll increase the kinetic energy by a factor of four thanks to that little square function there.

Momentum is defined as the product of an object’s mass and velocity. The formula looks a little bit like kinetic energy’s:

,

where is momentum (I don’t know why they chose

, but we can’t use

twice in the same equation),

is the mass of the object, and

the velocity.

It’s a little hard to define in words, but momentum is just a way to quantify the movement of an object. Where it differs from kinetic energy though, is that the momentum of a system is always conserved (in a closed system). What that means is that if you were roller-skating along a flat, friction-less road in a vacuum carrying a big bag of bricks (something we can all relate to) at a certain velocity, then dropped the bag of bricks, you would suddenly start moving faster. You had some momentum before, and since you’ve reduced your mass, your velocity has to increase to make up the difference in order to conserve that momentum. The closed system part just means that some other force isn’t acting on your object. For instance, if you set a ball rolling down a hill, you would see that it continues to get faster and faster, thus breaking the law of conservation of momentum. But! Since the Earth is doing work on the ball via gravity, the law of conservation doesn’t apply here.

Collisions in physics are divided into two categories: elastic, and inelastic collisions. The thing that separates them is the conservation of kinetic energy. Elastic collisions conserve kinetic energy, so that the total kinetic energy before and after a collision is the same. We see this in the case of those swinging Newton’s Cradle toys. When one ball swings into the rest, the energy is transferred across the row and kicks out one ball on the other side, with the same speed that the incoming ball had. Similarly, when you swing two balls into the row, two balls are kicked out the other side at the same speed. This seemingly continues on forever, but it does slow down and stop eventually because SOME of the kinetic energy is converted into other types of energy – sound and heat for instance. For the most part though, the Newton’s Cradle is a very good approximation of elastic collisions.

Inelastic collisions are collisions in which the kinetic energy is NOT conserved. An example often used for this type of collision is in the case of two cars crashing into each other, and becoming stuck together as one mass. Real life collisions often sit somewhere in between these two types of collisions – things don’t usually stick together, but do lose energy to things like heat, sound and deformation. In both cases however, momentum is always conserved. How does that factor into football tackles?

There are a lot of different cases to consider, but let’s assume for a moment that a tackler is moving toward a stationary target – a quarterback looking down-field for a receiver. Upon the hit, the tackler wraps his arms around the quarterback (ever so tenderly) and brings him down to the ground. Here, our conditions indicate an inelastic collision.

Conservation of momentum tells us that the total momentum before and after the collision are the same, so

,

where is the final velocity of both players stuck together, just after the hit.

But since the second player isn’t initially moving and , we can just say that his momentum is zero. Then,

It’s a pretty simple matter of solving for the final velocity, and it comes out to be

As for kinetic energy, we can’t just do what we did above and say that the kinetic energy before and after the hit will be the same – it’s not conserved here, remember? This time, we’ll do something a little more tricky: consider the ratio of the initial and final kinetic energies.

and

,

where is the initial kinetic energy and

is the final kinetic energy.

To consider the ratio,

Since we already know what is (we solved it with conservation of momentum), we can just plug that right into the kinetic energy equation. We get:

,

a huge mess that boils down to

.

We also get an expression for the amount of kinetic energy lost: . All of this basically says that the kinetic energy of a tackler will increase by less if the quarterback he’s tackling is a lot smaller than him. If the quarterback is larger, then the tackler will have to be travelling faster in order to successfully take him down. It’s all pretty much common sense.

Back to momentum real quick: when a collision happens, the total momentum is conserved, but the momentum of a single object is changed. This change in momentum is called impulse, and usually comes up when the velocity of an object changes. Impulse is then

for the fact that

,

from Newton’s laws of motion, where is force,

is acceleration,

is time, and

is the change in velocity.

What we can get from this is that the force of impact depends on how long the tackle takes. Since the change in momentum is a constant (you go from one speed to another), the force of impact and time trade off. What I mean is that increasing the time of impact will reduce the force of impact. Things like landing on grass, softening the blow with pads, and simply being squishy humans help to mitigate the force of a head-on collision. For the same reason, modern cars have “crumple-zones”, certain areas of the car that are designed to crumple up to absorb energy and increase the time of impact.

To no-one’s surprise, the saving grace in all of this running around and bashing other people’s heads in is the humble helmet and pads. Continuing development in those technologies might eventually eliminate the risk of injury in this sport, but I have a feeling that they’ll just allow us to keep on hitting harder. And everyone knows that hard hits are what make football worth watching in the first place.